The Gathering Bag, part 1: Remembering the heroines of traditional San stories

An extraordinary book explores a tender, intricate process of recovering story

Dear friends,

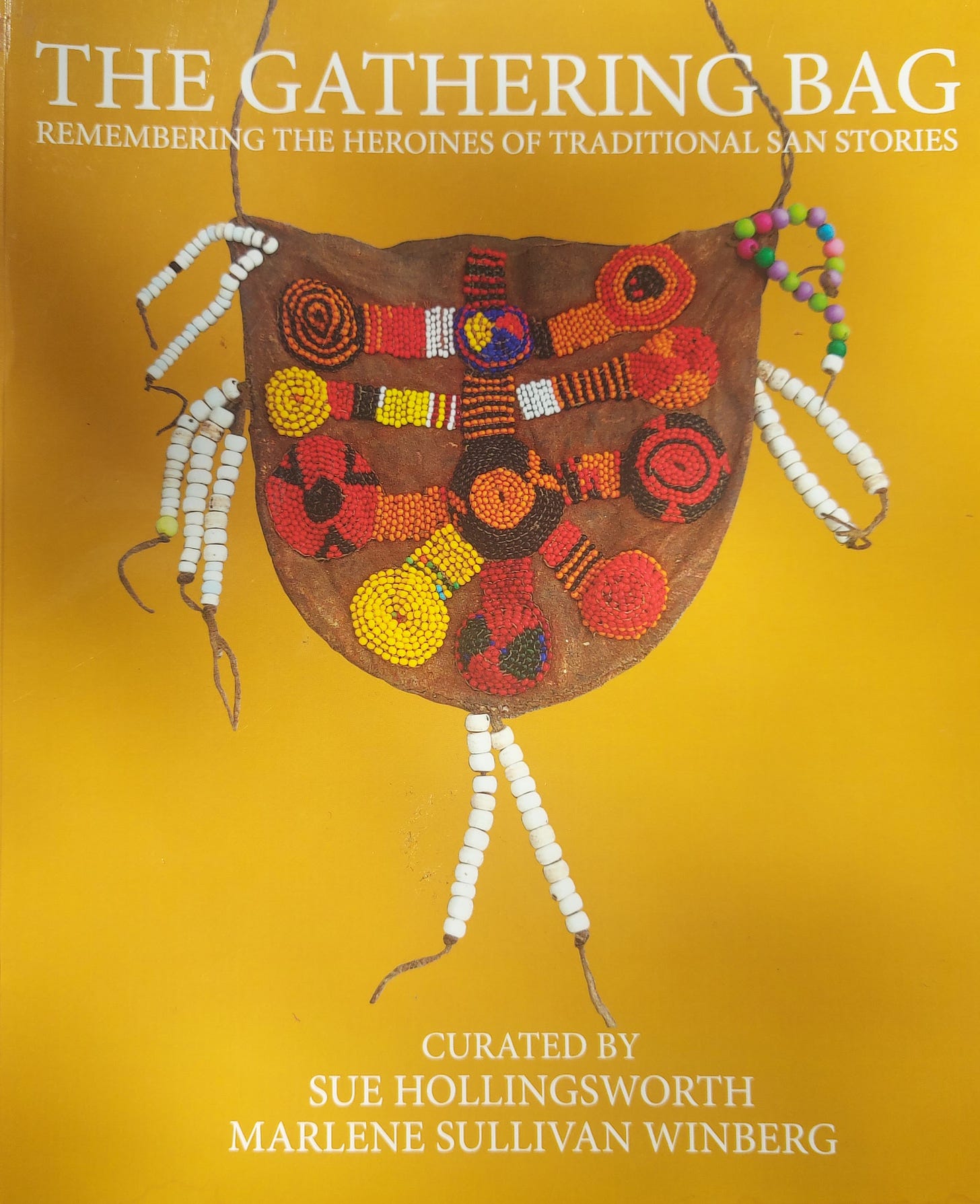

In the indigenous San cultures of Southern Africa, the gathering bag was an item of vital practicality and symbolism, carried by women and girls as they walked in the bushveld foraging for food. It was an intricately crafted animal skin pouch, adorned with patterns of bead and shell, and filled up with edible leaves, roots and berries gathered from the wild to nourish families and communities.

A woman’s gathering bag was an expression of her being and her relationships in the world. As described in an extraordinary new book entitled The Gathering Bag: Remembering the Heroines of Traditional San Stories:

‘The inside of the bag smelled of the animal and remained imbued with its power and spirit, holding stories of the one who may have gifted her with the skin, how he hunted it and what he experienced when the arrow pierced the animal’s heart. The bags contained metaphorical narratives about transformation, where a drop of blood could grow into a human being and back into a living animal. In her repertoire of stories, she likened the bags to her womb, seeing them as a symbol of creation, renewal and rebirth. The bags linked her, the hunter, and the animal — and connected her to the whole ecosystem of which she was a part.’

The book, curated by oral storyteller Sue Hollingsworth and narrative arts therapist Marlene Sullivan Winberg, similarly offers itself as a gathering bag — of story, of memory and of the magic of ‘languaging’ together in community. It holds the story of a decades-long process to bring ten stories traditionally told by !xun San women from southern Africa, passed down orally over many generations, to life in its pages. As those pages reveal, this was a delicate process that ultimately convened not only !xun storytellers, but storytellers from around the world — to invoke the participatory, community-building and meaning-making powers of storytelling — and to re-animate these ancient stories silenced by more than 30 years of war.

As Sue writes, “Abracadabra!” is an incantation invoking the power of the spoken word. It means “I create what I speak” — and is a spell to summon change or transformation in the physical world. As The Gathering Bag illuminates, stories often need the magic of the spoken word, combined with the listening of others, to be infused with life. I am lucky to have experienced this magical process of oral storytelling firsthand with Sue as my teacher!

In the book, the gathering bag serves as a metaphor for the essential stories and meanings that we all carry through our lives. To delve into the substance of any gathering bag — individually or collectively held — is to invoke tender questions of responsibility. I wish to acknowledge the particular sensitivity of writing about or working with the stories of San and Khoe peoples whose ancestral land is Southern Africa, and who have been dispossessed and subjected to violence over many generations, including the epistemic violence of erasure and misappropriation of their stories.

The Gathering Bag is offered as an honouring and upliftment of !xun women’s voices. After reading the book, I spoke with Sue to journey deeper into its themes. (Watch your inbox — I’ll share more of our conversation next week). For now, I want to share the story of how the stories in this book were brought to life. I also recommend listening to these two interviews, one with Marlene and one with Sue, by Nancy Richards for the Womanzone podcast.

Stories as medicine

The heroine stories of the book came from the memories of !xun elders, born in Angola and exiled to South Africa, who remained connected to their pre-colonial, ancestral places through oral stories passed from generation to generation. As Marlene writes in her introduction, the heroines of the stories give voice to a hunter-gatherer culture that experienced the animate and spiritual forces woven through life. In the stories, the women and girl heroines navigate a living world of beauty and danger. With bravery, determination and resourcefulness, they outsmart lions, ogres and feckless husbands. They shapeshift to evade predatory dangers. They journey to other realms, and enact powerful community healing processes. They confront their situations without flinching — and most of the time they return home to tell the tale.

Marlene listened to these stories while working over more than a decade with the !xun storytellers from Angola on an oral history project in the former army camp of Schmidtsdrift, South Africa. The storytellers belonged to a community in exile, forced to endure a cruel legacy from the previous apartheid regime’s wars across the region during the 1970s and 80s to secure its borders. During those border wars, !xun communities in areas of Angola and northern Namibia had been co-opted by the apartheid military forces, who used their formidable tracking skills to pursue enemies. Under years of brutal militarisation, the community’s traditional storytelling and trance practices were suppressed. As an elder !xun healer and storyteller named Meneputo Manunga Manyeka had said to Marlene, the stories had gone ‘quiet.’

This was a time of political change across the region. South African forces withdrew from Namibia in 1990, as that country claimed independence from the apartheid state. Thousands of !xun people were left vulnerable to reprisals, because they had been conscripted by the enemy. They were evacuated to South Africa — and as South Africa made its own transition to democracy several years later, in 1994, Marlene arrived at Schmidtsdrift as she was in a process of healing her own wounds.

She was a white, Afrikaans-speaking woman, who had resisted the ‘whites only’ categorizations of apartheid by immersing herself in indigenous African philosophies and creative practices expressed through dance, the arts and storytelling. Her cultural activism raised the suspicions of the apartheid security police. One day they raided her home, confiscating her collection of banned books and her private journal, locking her in solitary confinement. As she writes: ‘This experience was a startling personal revelation of how stories take on different forms depending on who tells them, who listens, and where they are told. A story can be manipulated to serve the intention of the person who tells it.’

At Schmidtsdrift, Marlene became fascinated by a group of !xun artists1, who she saw painting their lost memories of the natural world in bright colours and vivid patterns on canvases. Marlene wrote in her journal at the time: ‘Spontaneous designs jumped into my face and delighted my senses with scenes of trees, animals, fruits, bulbs, roots, leaves, flowers, gathering bags, people, bows, arrows and spears.’

She recognised people tapping their creativity through the arts and storytelling to transform their narratives of pain. Meneputo Manunga Manyeka was an elder and storyteller in the community, bearing the title of ‘Manyeka’, meaning doctor — with whom Marlene developed a special bond. As Marlene recounted in her interview with Nancy Richards:

‘I was so fascinated by the stories and the songs and her entire healing practice, that I couldn’t stop going there. I was called, it was like a compulsion. She had an entire healing practice in her tent in Schmidtsdrift. It consisted of song, of dance, of stories, of herbal medicines. And I got to be lucky enough to witness all of this. She couldn’t speak English and I couldn’t speak !xun, so it was a very long, slow process of me learning enough !xun words to be able to understand at least the basics. And I think that after a while, she probably decided that I had been around for long enough that she will let me in. And then one of the biggest discoveries that I made was that she had specific stories that came through her trance dancing, and that she would administer as medicine to the people around her.’

As Marlene gathered more and more stories in her oral history work with the community, an intricate process of transcribing and translating the stories developed. Elders would tell their stories in the !xun language, while their teenage children, who could read, write and speak in Afrikaans, would transcribe the stories into Afrikaans. Then the teenagers spoke the stories they had transcribed back to their elders in !xun. Once the elders had confirmed the accuracy of the teenagers’ transcriptions, Marlene would translate the corrected texts from Afrikaans into English.

Stories re-animated

Marlene had promised Meneputo that she would compile the stories into a book so they would not be forgotten. As a folklorist, she also grasped the stories’ wider significance to the world as oral literature from an ancient wisdom tradition. As she writes in the book’s introduction:

‘The stories are symbolic reflections of every woman’s life, my own included, as I track the psychological routes to harmony in my personhood, family, community and the world I live in. They allow me to enter the metaphorical wilderness of my own humanity, the places that are chaotic, raw, dangerous, unpredictable, broken and beautiful, like the world in which I live. I have come to embrace the !xun women’s stories as valuable historical documents that bear witness to how women have made sense of the confusion and rhapsody of life through storytelling.’

Marlene didn’t want to create a book from the stories that would become simply another collection of folklore. She wanted to know how modern women outside of the !xun community would experience these stories and find resonance with them.

That is where Sue could help. As an international storyteller with a global network, Sue could send each of the ten stories out to a modern storyteller somewhere in the world who would work with that story and reflect on it from her own perspective.

As Sue was to discover, this was no simple undertaking. The stories had always been spoken in the rhythm and poetry of the rich, complex !xun language. Bringing the stories to the written page, however, had stripped them to their bones. How could these sparse, flattened texts even begin to evoke the wild and animate world through which the !xun women walked with all of their senses alive and singing?

As Sue writes in her introduction to The Gathering Bag, the stories had become separated from the ‘the powerful spell of the spoken !xun language’.

‘It had severed them from the storyteller’s glance, their tone of voice and gesture. It had also separated them from the natural landscape in which they were meant to be heard, in which they made sense. The !xun, who had never had an alphabet, had never had to separate themselves from the sound, smell, shape, colour and threat of a lion, for example, and reduce it to a series of marks on a flat surface.

Each of the ten stories travelled to a storyteller in New Zealand or Australia; in Japan, India or Turkey; in South Africa, Greece, Spain or Mexico. The final one went home with Sue to Britain. The plan was for each storyteller to write a 500 word reflection about the story she was given — but this was not a task to be accomplished individually or in isolation. As Sue writes:

‘There are at least three ingredients to the magical process of bringing oral stories back to life from the written page. They are a fire, a circle of listeners and the storyteller’s imagination, a recreation of our ancient, pre-literate storytelling roots.’

As luck would have it, it was the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. Suddenly, just as the !xun people exiled to South Africa had been uprooted from their worlds, Sue found herself cut off from her world by the pandemic. She felt lonely, vulnerable and isolated. ‘I felt I was wandering in the underworld, silenced, without a voice. The separation of the stories from their physical landscape and cultural background was mirrored by my separation and isolation from the community of those I loved.’

In such a difficult time, Sue realised she needed to find a way of bringing together the international storytellers she had enlisted so that they could work collectively to breathe flesh and blood life back into the stories.

Like so many others during the pandemic, she turned to Zoom. Over the next year, the international storytellers came together in a virtual circle, lit their candles, and told their stories to one another. As Sue relates in The Gathering Bag, working with a story to tell it to listeners is a process of creating wholeness. Each story evokes a world that must be imagined and animated through the sensibilities of the storyteller. Oral stories translated to the page have gaps; they fragment and get lost in translation. They raise questions and present puzzling enigmas or parts that don’t quite seem to make sense. The task of the storyteller is to work deeply with a story — living it, breathing it, walking with it, imagining it, telling it to others — in order to gradually resolve its fractures and restore it to life and wholeness.

As Sue relates, this is both a process of inner work, of finding your own resonance with the story — and it is a collective, participatory process. The robust, collective engagement with the stories in the Zoom gatherings brought them alive. People laughed and wept and shared stories from their own lives as these were evoked by the !xun tales. The story of The Elephant Wife provoked outrage with its themes of femicide and human aggression towards animals. While the tale of The Sisters and the Ogre raised laughter and discussion of the difficult sexual situations women face. As Sue recalls, this was a collective process of drawing out the wisdom in the !xun stories, and making it palpable for women living in the 21st century. As Sue writes, the Zoom dialogues brought the voices of the !xun heroines alive, so they ‘spoke directly to us, woman to woman.’

As a reader, I loved glimpsing all these different layers of story, meaning and context that were part of creating the book. The words on the pages came alive in my imagination, as did the different voices of all the women who contributed to the project. Immersing in the words, photographs and artwork in the book gave me at least a glimmer of the magic in the journey of this process.

So I will leave you with this reflection from Sue, which sets the scene for the conversation that she and I had, which I will share next week:

‘We are all nomads on the journey of life. When we gather together to listen to stories, we create the possibility of filling in those gaps between us. We may start as strangers, but once we start speaking together, we reconnect through the reliving and re-membering of the story itself. This is a subtle form of healing. When we light the fire and gather in a circle for food, companionship and stories, as we have done for thousands of years, we become part of an ancient community of listeners. A community not just of human beings but of all beings: animals, plants, mountains, oceans, stars and our ancestors. Differences drop away in the dusk, all things become possible and we are rewoven together into one all-encompassing story.’

Until next time, I’ll be thinking of how my own story touches into this one all-encompassing story that holds us all. I'll be thinking about the contents of my gathering bag. As I now journey through mid-life, I find I take different kinds of nourishment into my gathering bag than before. I notice myself wanting to travel lighter, with more discernment about what I take and what I leave on the land for the next creature to harvest. I want to keep things simple, and move to my own rhythms rather than the ones society demands. What about you? What stories, memories and experiences are you carrying? How are you filling up your gathering bag as you journey through this life?

With love,

Megan

https://www.artprintsa.com/Xun-and-Khwe-Art-Project.html