The Gathering Bag, part 2: in conversation with Sue Hollingsworth

An exploration of intuition, listening, feeling into the skin of another, and the possibilities for community and ecological healing

Dear friends,

Last time, if you missed it, I wrote about an extraordinary book called The Gathering Bag: Remembering the Heroines of Traditional San Stories. It is a book of ten indigenous !xun women’s stories from southern Africa. The link to my first article is here.

For this article, I had a conversation with the book’s co-curator, Sue Hollingsworth. Sue is a storyteller, teacher and coach whose passion for storytelling as a community building art and practice is infectious. I trained with Sue in oral storytelling myself several years ago. She is also co-author of the Storyteller’s Way: A Sourcebook for Inspired Storytelling with Ashley Ramsden. Based in Wales, she travels regularly to South Africa and around the world, performing stories and teaching and mentoring other storytellers.

Sue and I had a wide-ranging conversation reflecting on the book, with a thread of ‘intuition’ woven throughout. We explored the perspectives of the !xun heroines in the stories — and spoke of Sue’s own journey and collaboration with narrative arts therapist Marlene Sullivan Winberg to produce the book. We spoke of the beauty and sensitivity of working with the living stories of communities — and the ethics of care that emerge from offering oneself as a dedicated story listener. Sue also spoke to the possibilities of personal, community and ecological healing through storytelling.

Each of the book’s ten stories was told orally by an indigenous !xun Angolan-born storyteller, and then transcribed in an intricate, intergenerational process of translation that was facilitated by Marlene during her work on an oral history project with the community over the first decade of South Africa’s democracy.

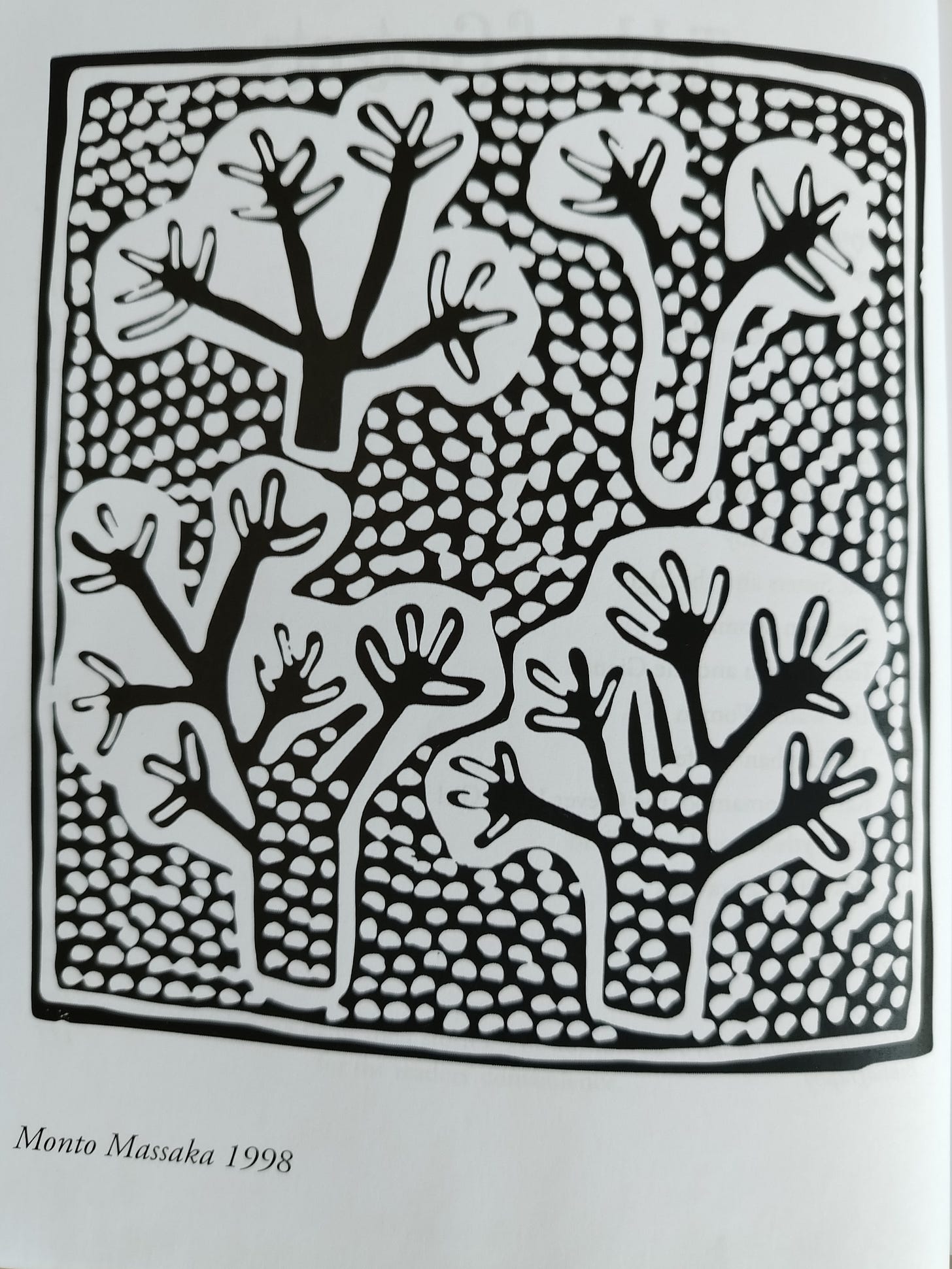

Sue’s part in the project came much later. She matched each traditional story with a contemporary storyteller from some other part of the world, and then she convened the modern day storytellers to re-animate the stories they’d worked with in a series of gatherings on Zoom. All of this is beautifully described in The Gathering Bag book, with art, photographs and written stories expressing the distinctive voices of each storyteller who took part.

As I read The Gathering Bag, I felt the workings of intuition everywhere in its pages. To me, intuition is a mysterious quality that guides a creative, relational life. I see it emerging from deep listening and attunement, and flowing from carefully cultivated inner and outer knowing, enabling intelligent response to things that escape our ‘rational’ minds.

I asked Sue to speak about her relationship to intuition in the process of creating the book. Sue recalled that when she and Marlene first met, a full moon was rising before them above the sea at dusk:

My most potent symbol of the feminine and therefore of intuition is the full moon. I had only met this woman maybe 45 minutes beforehand. I was aware that the quality of the silence that fell over us while we watched the moon rising had a very comfortable feeling. We were both completely focused on the moon. For me that was a moment of complete activation of my intuition. I woke up, as it were. I thought, oh, who am I with? Because I think this might be someone important. We might have things to do together. We’re two women looking at my most potent powerful feminine symbol coming up in front of our eyes out of the ocean of unconsciousness!

I think everything that followed came from that. Right at the beginning of a journey with a project or a person or place, when you have such a strong or powerful intuition, really the rest just goes on from there. You have to follow it!

As Sue spoke of this moment of recognition of her own intuitive voice, I was reminded of places in the stories where I felt the heroines similarly recognising their intuitions. In the story of The Lion Woman, told originally by !xun storyteller Kashivi Rumao, a healer’s assistant who in Angola had personally attended many people wounded by lions, a woman wakes up one morning and simply decides to leave. This was the story that Sue worked with. Fed up with an unsupportive husband, the woman in the story undertakes a solitary journey that brings her face to face with a fierce lion in the dead of night. Sue elaborates:

What really grabbed me in the story was the way this woman just stood up and left one morning before the sun comes up. She must have just woken up in the night and thought, it’s now or never! I can totally relate to that! She just picked up her things and was gone! I thought, this is so bold! It looks like a very adventurous move, but actually I feel like it was coming from a very deeply intuitive place.

Many of the stories have quite a lot of action in them. I love that. The women have agency, they’re not passive, they take strong actions. It may seem on a superficial level that they’re not working from their intuition, but oh my God, I think they really are!

In another story, Katitu Momambo the Clever Little Girl, a young girl and her sisters are being chased by a monster. In a decisive moment, the girl tells her sisters to turn themselves into trees. Sue observes:

She speaks to her older sisters in a commanding way, which is what takes the attention and tells you that she is a clever little girl. She says: ‘turn into trees’. You can see that as a way of her taking control and having agency, which are very masculine qualities. But why does she say, turn into trees? And why are there so many stories throughout the world about women turning into trees? There’s something deeply intuitive about it. So for me, even in that command, just like with the Lion Woman, in what looks like a very masculine moment, there’s also something so deeply intuitive.

In another story, The Python and the Little Child, a horrific situation arises as a group of women are filling their gathering bags with ripe red berries to take home. One woman puts her small child down on the ground so she can fill her bag up with fruit. Behind a clump of bushes, the child sees a python and cries out for her mother. But the mother keeps working, explaining to the child that the family went to bed with empty stomachs the night before, so she must gather food. As the child cries out again and again, the mother keeps telling the child to be quiet, to be good. Only after her bag is full does the mother return to find her child — but instead she notices a python with a huge bulge in its long body!

The other women come running when they hear her screams, and frantically push their digging sticks down the python’s throat, forcing it to vomit and saving the child’s life. The story ends with the words: ‘The women killed the huge snake and took it home, where they cut it up and roasted it on the fire. They ate berries and soft meat that night. They talked about the python and how it had swallowed the child. They talked about how the mother had left her child alone and how they had saved the child and killed the snake. They talked and talked and talked.’

As Sue observes, this ending illustrates the deep intuitive knowledge of the women in the story as they recognise a need for collective healing through dialogue. After the traumatic ordeal, the other women realise that the young mother who left her child needs to be with them; she needs to have the chance to tell her story and express her feelings about what happened. Sue elaborates: ‘They need to talk about how the other women are around and can help. They need to process the experience and work through it. In the telling of the story, it becomes something that happened, and not something that’s alive in the community still.’

As I wrote last time, the healing and integrative rituals of telling and listening to stories in community are an important motif of The Gathering Bag. As Sue spoke about the role of the women in the python story as listeners, I was reminded of Marlene’s role as a story listener as she worked with the exiled !xun communities in South Africa to help facilitate their recovery of their stories in the aftermath of war. I asked Sue to share her reflections on the role of a story listener within such delicate processes of collective healing. Sue spoke of a deep understanding within many African cultures of the power and importance of collective healing processes, evident for example in the work of Malidoma Somé and Sobonfu Somé with the healing rituals of the Dagara people of Burkina Faso. On this subject, Sue explains, Africa has much to offer the rest of the world:

In the west we generally undertake those healing journeys, especially from trauma, in a very lonely way — often with just a therapist. I feel like the power of many cultures from southern Africa and other parts of Africa, lies in their understanding that there is something very powerful that can happen when a group of people comes together with a healing intention.

What’s interesting is, you need the community, but you also need someone for example like Marlene who is giving a certain validation to the experience. This is very sensitive obviously because it goes back to South Africa’s deep and difficult roots. To be listened to by a highly intelligent and deeply sympathetic and deeply interested white, Afrikaans woman, there is validation in her being there. And then there is this deep, intuitive wondrous power that Marlene has of listening that she brought to enable her to be trusted with the things people had to say. If you are traumatized, you can’t just spill the beans to everyone, because most people will not have the understanding, will not be able to have the empathy to realise what it means to be living in a war torn country and have to leave with all your possessions and your children.

So you need a potentizer, I would call it: a person who is willing to be the focus for the listening, for the healing. It can’t be hurried, so it’s got to be someone who is willing to commit for the long term. Marlene took a decade or more to build up the trust to enable people to speak to her in this way.

As Sue later convened the international storytellers over Zoom to tell and talk about the traditional !xun stories, she became the potentizer. As Sue reflects, the work of a storyteller is to feel deeply into the skin of another, to shapeshift and experience the world through other embodied perspectives. In the virtual story circle, as the stories were collectively felt, re-animated and re-infused with life, their healing powers were restored through the enactment of community. Sue reflects:

For me as a storyteller, whether I’m performing or teaching or coaching, the potential for healing is always there. That’s why I normally do my coaching work with an individual in front of a group, because the group is so important in the strength that it gives that person who’s upfront and having the coaching. It gives them strength and insight and intuition to make the leap — because sometimes when we’re working on our own stories we can be so stuck. It’s only the listening from other people that can help us shift to some kind of profound realisation. People often make the mistake of thinking that it’s coming through me because I’m the teacher, but I’m just the potentizer. It’s coming through the whole.

As Sue observes, storytelling touches into the power not only of the imagination — but of the invisible. In the stories, healers in the community are guided by ancestors and the spirit realm. In one story, The Water Woman, a young woman disappears into the river and cannot be found. The healers of the community, guided by their ancestors, know that she has gone to another realm beneath the water, and that her calling is to mediate between the worlds above and below the water. When the woman finally comes back to the community, she tells them she has become a healer. Sue observes:

She has her child from that other world and she tells them about her union with the water snake. The community witnesses her role as a healer, but there is another community that is part of that story which is completely invisible. When she is taken down below the water, she is not alone down there either. It’s not told in the story, it’s left to us to use our intuition to be present to the fact that when she went under the water, she also became part of a community down there. There’s an invisible community in the spiritual world that she became part of. It’s really important to name that, because I think the presence of the invisible ones, whatever nomenclature you want to give it, is also part of our being and our work.’

As Sue observes, the power of the invisible often comes forth in darkness, when our clarity of vision is obscured:

‘For me the shapeshifting happens at that dusky time of night when you can’t quite tell the difference between things. As human beings we have two eyes in the front of our head — our main dominant sense is sight. To survive, we have to have a powerful sense of discrimination — is something a danger or is it not? But when our sight becomes blurred and we can’t quite tell what something is — it could be a human or it could be an animal. This is really the potent storytelling time. That’s why I think a lot of healing rituals happen at night. Our strongest sense is out, and we have to rely on this intuition, this other sensing. It holds us in this place of wonder and of suspension of knowing. I think that’s a very potent place to be’.

What comes up for me, as Sue speaks to these capacities of sensing, intuition and empathy that enable storytellers to mediate between worlds and slip into the skins of others, is ecological. We modern humans are destroying the living earth, and I think this is partly because so many of us have lost our capacities of feeling for more-than-human life. I have often felt that storytelling restores me to wider ecological relationship and community. When I work with a story, preparing to tell it to people, I must walk among trees, or at the sea. I feel very connected to the plants and trees and birds and other animals as fellow beings within the body of the earth. I need such encounter to escape the gaze of modern rationality and sink myself fully into the story. When I bring this up with Sue, she responds:

For me as a storyteller, it seems there’s really no way forward unless we can enter in to the skin of the earth, into the skin of the animals which are being hunted to extinction or are losing their habitat. Unless we can enter in and feel what’s going on, I don’t think we’re going to be very successful, because it’s all going to be very head-based. A lot of environmental activism for me utilises the very things that have brought about the problem. I’m very much for a different approach. Yet I think there are two problems with this: first of all, it’s slow, and secondly, it’s painful.

Let me address the slowness first, because I think that’s where walking comes in. I often go for a walk with a story, and I walk a lot. It slows you down and it allows you to make contact with other things which are slower too. Most of the things connected with the earth itself and plants, they are a lot slower. Even with animals, there’s a very different speed of thinking, instinctiveness and movement. There is something about walking that slows everything down for me and allows me to put myself in the right frame of mind.

But then I think the other thing is more difficult, because if you do slow down and you do start to slip inside the skin of the earth or other animals, I think what you feel is enormous pain. And I think as human beings, what I’ve noticed in most of the stories, whether they’re traditional or true, is that we will do anything to avoid pain. It takes a lot to bring us to the point where we look the pain in the face. We’ll do all kinds of stuff to avoid dealing with it, whatever it is. So how can you get people to slow down? Because if you do, they will experience the pain. And I think personally speaking, the pain is overwhelming. I can barely allow myself to touch into it. It’s just too traumatic for me most of the time.

The thing about story is it does let you train that faculty of being able to slip into the skin of another being, or a rock, or a comb, or any object. It develops that faculty gradually, so that maybe we’re able to slip under the skin of the big things. I think the environmental crisis is perhaps a bridge for us to develop those faculties in a way that wasn’t needed in the past, but now it definitely is.

Sue’s reflections bring our conversation back to the particular gift that Africa offers the rest of the world, through its cultures of collective storytelling and ritual as ways of resourcing people to face pain and enable healing. Sue continues:

That’s what happens when communities come together to heal trauma — we’re connecting with a person’s pain — all of us. Now we all have to connect with the earth’s pain, and it’s just awful.

You made a really important link in everything we were talking about which is collective healing of trauma, whether it is an individual being witnessed by a group, whether it’s a storyteller telling a story to an audience or working with a story in a group, or whether it’s us gathering on Zoom — to talk about the stories, laugh about them, cry about them, be outraged about them. Then we were saying how we’ve got to dare to develop this faculty with the more than human, to slip under the skin, the shapeshifting — it takes a lot of time and a lot of patience and you’ve got to be willing to accept the pain you find on the other side of that. It happened for Marlene; there was a lot of pain in that community. It’s the same with this possibility of building a bridge with the environment. If we go there, if we enter in, we will have to deal with that.

My experience at the moment is that it is very rare people who can accept and deal with the pain they find in those situations. That’s why I think we should be looking at what goes on in the African continent. There are so many indigenous, collective rituals for the healing of trauma, of which of course telling stories is one.

This brings us back to The Gathering Bag. As Sue explains, one of her intentions with the book was to inspire readers to undertake their own gatherings to read and tell and speak about the stories. She elaborates:

My dream with the Gathering Bag is to spark off gatherings of women, gatherings of people who are not women — to be with each other and be with the stories. The stories contain big themes, and if you’re willing to go down into them there is quite a lot of pain and trauma to be experienced, as well as a lot of joy and wonderment and other things as well.

My dream is that the gatherings could come from the Gathering Bag. What you’ve touched on is part of the reason why I really struggled to write my piece in the Gathering Bag. I was alone and I’m a very relational person and it was during the COVID lockdown. I couldn’t really see clearly what my role was in all of this. Marlene could. I thought I could just be the person who puts her in touch with the international storytellers, and helps her sort out which story should be for which storyteller. And I would take one of the stories and write something. But I couldn’t see any other role. Marlene was convinced that there was another role for me, but it took me so very long to find it, and it came accidentally through COVID. I need to be with people. I find it very difficult to work without community. I find it much easier to think when I’m with others.

I think Marlene intuitively realised that — talking about intuition again! She let me find my way, and COVID showed me that I just had to bring everyone together. Once I’d got everyone together and we had this process, it became very easy for me to see what I needed to write about! We can’t do it on our own, and what that could mean in how we could resource ourselves in any future time of isolation. It wasn’t perfect on Zoom — it never is — but it allowed me to enter into the stories, to connect around the world, and it gave me what I’m passionate about and what I wanted to write about: that process of connecting with others, and that we need others! I say that people drop through gaps in our society. The stories and the listening mean that you cannot end up alone — whether it’s the people you’re with or the characters in the story — it can be through the plants, the animals, anything — you can find the healing that comes through being together. For me that’s what it’s all about.

And with that, dear friends, I invite you to the Gathering Bag! Are you inspired to gather your own community to experience these stories collectively? You can find your own copy of the Gathering Bag here. If you do read it, or better yet engage with the book in a group, please let me know what that experience is like for you!

With love,

Megan

P.S. If this work touches you, please share it widely! It has been a joy to share my passion for Living Stories with all of you over these last three years. Knowing that there is a small but growing community of readers around the world who value Living Stories — some of whom I know, and many of whom I don’t know! — inspires me to keep writing! Thank you!